In the intricate dance of life, organisms have evolved sophisticated internal timekeeping mechanisms known as circadian clocks to anticipate and adapt to the daily cycles of light and temperature. Among model organisms, Arabidopsis thaliana has emerged as a pivotal system for unraveling the mysteries of these biological rhythms. Recent research has deepened our understanding of a remarkable feature of the plant's circadian clock: its ability to maintain period stability despite fluctuations in ambient temperature—a phenomenon termed temperature compensation.

The circadian clock of Arabidopsis, like those in other eukaryotes, operates through a complex network of interconnected feedback loops involving key genes such as TOC1, CCA1, and LHY. These components regulate physiological processes, from photosynthesis to flowering time, ensuring optimal performance relative to external conditions. What makes temperature compensation particularly fascinating is its counterintuitive nature; while most biochemical reactions accelerate with rising temperature due to increased molecular kinetic energy, the circadian period remains remarkably constant across a physiological range. This stability is not merely a passive trait but an actively regulated property essential for the clock's reliability as a predictive tool in natural environments where temperatures can vary significantly between day and night or across seasons.

Investigations into the molecular underpinnings of temperature compensation in Arabidopsis have revealed a multi-layered control system. Post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation and ubiquitination, play critical roles in fine-tuning the clock's pace. For instance, the protein kinase CK2 modulates the activity of key clock components like CCA1, altering their stability or nuclear localization in response to thermal cues. Additionally, alternative splicing of clock genes, such as PRR7 and PRR9, generates isoforms that may function differentially under varying temperatures, adding another layer of regulatory flexibility. These mechanisms collectively buffer the clock against thermal noise, ensuring that the period deviates by less than a few hours over a range of 10-30°C.

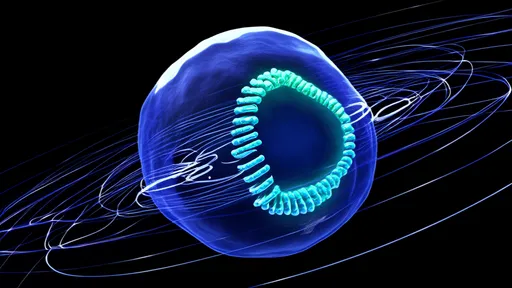

Beyond molecular adjustments, structural aspects of the clock network contribute to its robustness. The interconnected feedback loops exhibit redundancy and mutual regulation; for example, the morning-phased genes CCA1 and LHY repress evening-phased genes like TOC1, which in turn feedback to activate CCA1 and LHY. This architecture allows for compensatory adjustments—if one loop is perturbed by temperature, another can counterbalance the effect. Computational modeling has supported this view, showing that network topology itself, rather than any single component, is fundamental to temperature compensation. Such resilience highlights the clock's evolution as a system designed to prioritize stability over sensitivity to transient environmental changes.

The ecological implications of temperature compensation are profound. In nature, Arabidopsis thrives across diverse latitudes and climates, from temperate regions to subarctic zones, where diurnal and seasonal temperature variations can be extreme. A compensated clock enables the plant to accurately measure day length for photoperiod-dependent processes such as flowering, ensuring reproductive success. Without this stability, fluctuations as simple as a cool night or a warm day could disrupt timing, leading to mismatches with optimal conditions for growth or pollination. Thus, temperature compensation is not just a laboratory curiosity but a vital adaptive trait that underpins fitness and survival in real-world scenarios.

Recent experimental approaches have leveraged genetic screens and high-throughput phenotyping to identify novel players in temperature compensation. Mutants with altered period lengths under temperature shifts, such as those affecting the ELF3 gene, have provided insights into how specific proteins sense and integrate thermal information. Interestingly, some components appear to have dual roles in both light and temperature signaling, suggesting an integrated network for processing multiple environmental inputs. Advanced techniques like luciferase reporter assays have allowed real-time monitoring of clock gene expression under controlled thermal regimes, revealing dynamic reponses that are often nonlinear and context-dependent.

Looking forward, challenges remain in fully dissecting the temperature compensation mechanism. While key genes and modifications are known, the precise biophysical processes—such as how protein conformational changes or RNA thermosensors contribute—are still being unraveled. Moreover, climate change adds urgency to this research; understanding how plant clocks cope with increasing temperature variability could inform strategies for engineering crops with enhanced resilience. The Arabidopsis clock, with its well-mapped network and genetic tractability, continues to serve as a blueprint for exploring these questions in other organisms, including humans, where circadian disruptions link to various health issues.

In summary, the temperature compensation of the Arabidopsis circadian clock exemplifies biological ingenuity—a system that maintains temporal precision amid environmental unpredictability. Through a blend of molecular tweaks, network buffering, and evolutionary tuning, this humble plant achieves what engineered systems often struggle with: reliability under fluctuation. As research progresses, each discovery not only deepens our appreciation of circadian biology but also opens doors to applications in agriculture, medicine, and beyond, reminding us that nature's timekeepers are as robust as they are elegant.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025