In the relentless pursuit of effective countermeasures against SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists have cast their nets into unexpected waters, uncovering a potent ally in the most ancient of vertebrates: sharks. The emerging frontier of nanobodies derived from these marine predators is rewriting the rules of viral neutralization, offering a glimpse into a future of robust and adaptable therapeutic interventions.

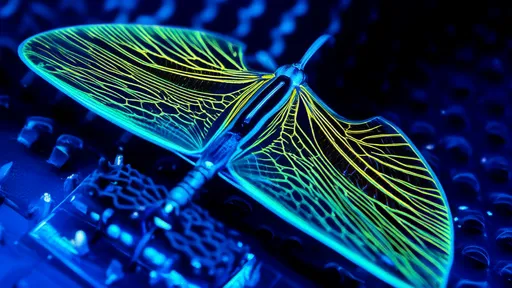

The story begins not with the complex immune systems of mammals, but with the simpler, yet remarkably effective, adaptive immune response found in cartilaginous fish like sharks. Unlike humans who produce conventional Y-shaped antibodies, sharks generate a unique, smaller class of antibodies known as Immunoglobulin New Antigen Receptors (IgNARs). A single domain of these IgNARs, the variable new antigen receptor (VNAR) domain, functions as a standalone binding unit—a nanobody. These shark-derived nanobodies are among the smallest naturally occurring antibody fragments known, a characteristic that bestows upon them a significant strategic advantage.

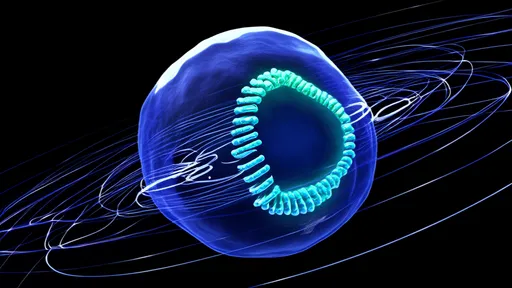

The power of these diminutive agents lies in their unparalleled access to cryptic epitopes on the viral surface. The receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is the primary key it uses to unlock and enter human cells via the ACE2 receptor. While conventional antibodies are often too large to effectively block every nook and cranny of this interface, shark VNARs, with their compact size and elongated, finger-like complementarity-determining regions (CDRs), can worm their way into grooves and clefts on the RBD that are otherwise inaccessible. This allows them to act like a master locksmith, inserting a precision pick to jam the viral key, thereby preventing its engagement with ACE2 with astonishing efficiency.

Research has illuminated several distinct mechanisms of neutralization employed by different shark VNARs. Some are classical competitive inhibitors, binding directly to the very tip of the RBD that makes contact with ACE2, creating a straightforward steric blockade. Others are more cunning, acting as allosteric inhibitors. These nanodies bind to a site distal to the ACE2 interface, but their binding induces a subtle conformational change in the spike protein. It is akin to bending the key just enough so it no longer fits the lock, effectively disabling it without ever touching the keyhole itself. This multifaceted approach to neutralization makes it exceedingly difficult for the virus to mutate and escape, as it would have to alter multiple, structurally constrained sites simultaneously.

Beyond their direct neutralizing prowess, the biophysical properties of shark VNARs are a bioengineer's dream. Their small size translates to exceptional tissue penetration and rapid clearance, which could be crucial for targeted delivery, such as in inhalable formulations for direct lung treatment. Furthermore, they exhibit a remarkable resilience to extreme conditions, including high temperatures and low pH, a trait honed by the shark's harsh physiological environment. This inherent stability simplifies manufacturing, storage, and distribution, bypassing the complex cold-chain logistics that plague conventional biologics. Perhaps most importantly, their simple, single-domain architecture makes them highly amenable to genetic engineering, allowing for the creation of multivalent, multi-specific molecules that can target several viral variants or mechanisms at once.

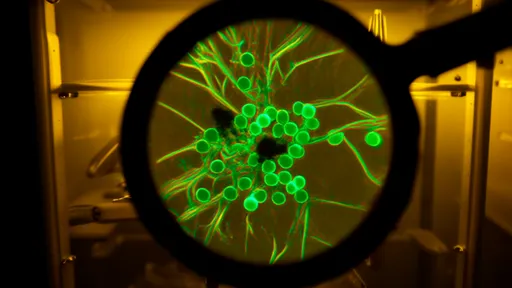

The journey from the shark's immune system to a potential human therapeutic is a testament to innovative scientific exploration. It involves immunizing sharks or using phage display libraries built from shark VNAR genes to identify candidates with high affinity for the SARS-CoV-2 spike. The lead candidates are then produced recombinantly in microbial systems like E. coli, which is far more scalable and cost-effective than mammalian cell culture used for traditional antibodies. This pipeline not only accelerates development but also aligns with ethical considerations by minimizing the need for repeated animal use after the initial genetic discovery.

While the promise is immense, the path forward is not without its challenges and considerations. The foreign nature of shark proteins raises valid questions about potential immunogenicity in humans—could the human immune system recognize these therapeutic nanobodies as invaders and mount a counter-response? Extensive preclinical and clinical testing will be essential to answer this. Furthermore, the scalability of production, while easier than for conventional antibodies, must be perfected to meet global demand. Finally, a rigorous ethical framework must govern the sourcing of these biological blueprints to ensure the conservation and welfare of shark species, leveraging modern biotechnology to avoid any detrimental impact on their populations.

In conclusion, the exploration of shark nanobodies represents a paradigm shift in antiviral strategy. They are not merely smaller antibodies; they are a different class of weapon altogether, leveraging unique size, stability, and engineering potential to outmaneuver a rapidly evolving virus. As the world continues to grapple with COVID-19 and prepares for future pandemic threats, these ancient biological marvels offer a powerful and versatile new arsenal. They stand as a powerful reminder that sometimes, the most advanced solutions are found not by looking forward, but by looking back to the deep and ancient wisdom of nature's own design.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025