The landscape of structural biology shifted seismically this summer when DeepMind's AlphaFold2 stunned the scientific community with its unprecedented accuracy in predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences. For decades, this problem—the protein folding problem—had been one of biology's grandest challenges. Yet, in the triumphant wake of this achievement, a significant frontier remained largely unconquered: the intricate and vital world of membrane proteins.

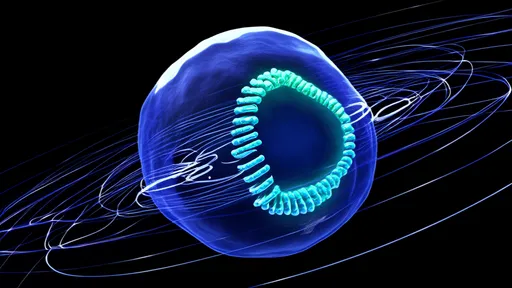

These biological gatekeepers, embedded within the fatty membranes of cells, are notoriously difficult to study. They are fundamental to life, governing how cells communicate with their environment, controlling the flow of ions and molecules, and serving as prime targets for over 60% of all modern pharmaceuticals. Their hydrophobic nature makes them recalcitrant to the traditional, gold-standard method of structure determination, X-ray crystallography. Obtaining a high-resolution structure for a single membrane protein could represent a decade of a PhD student's toil. This bottleneck has severely hampered drug discovery and our basic understanding of cellular machinery.

Enter the David to AlphaFold's Goliath: a consortium of researchers from the University of Washington's renowned Institute for Protein Design. Their tool, RosettaFold, has long been a powerful and widely used workhorse in the computational biology community. While AlphaFold2's performance was a monumental leap, the team in Seattle did not see it as the finish line. Instead, they recognized it as a new starting point, particularly for the thorny issue of membrane proteins. Their response is not merely an update; it is a targeted revolution. The newly unveiled RosettaFold2 represents a sophisticated retooling of their AI engine, specifically engineered to crack the code of these elusive molecules.

The breakthrough of RosettaFold2 lies in its novel architectural approach. While its predecessor and other models were trained predominantly on soluble, globular proteins, this new iteration ingests a diet rich in membrane protein data. The developers implemented a specialized training regimen that teaches the algorithm the unique physical and chemical constraints of a lipid bilayer. It learns that certain amino acids prefer to face the fatty interior of the membrane, while others point into the watery cell interior or exterior. It understands the specific angles and packing densities that helices adopt within this confined environment. This is akin to training a master architect not just on building free-standing houses, but specifically on designing foundations and structures that are stable within the soft, shifting ground of a marsh.

Early benchmarks are nothing short of spectacular. In blind tests against recently solved membrane protein structures that were not included in its training data, RosettaFold2 demonstrated a level of accuracy that begins to approach experimental resolution. It is correctly predicting the number of transmembrane helices, their precise tilt and rotation within the membrane, and the intricate loops that connect them. For G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)—a massive family of membrane proteins crucial for signal transduction and a key drug target—the model is showing remarkable success in placing specific side chains that are essential for drug binding. This is a game-changer. Researchers can now generate highly reliable hypotheses about a membrane protein's structure in a matter of hours, a task that previously could take years and millions of dollars.

The implications of this advance are profound and immediate for the field of drug discovery. The pharmaceutical industry's pipeline is littered with promising compounds that failed because of off-target effects or an incomplete understanding of their target's structure. With RosettaFold2, medicinal chemists and structural biologists can now generate accurate models of previously obscure drug targets. They can perform in silico docking screens to predict how millions of potential drug molecules might fit into a protein's binding pocket, all before synthesizing a single compound. This massively accelerates the initial, most expensive phases of drug development and increases the odds of success, potentially bringing new therapies to patients faster and more cheaply.

Beyond drug design, this technology opens new vistas in basic science. Scientists studying neurological disorders, cardiac function, or cellular metabolism are often stymied by the proteins involved because they are embedded in membranes. RosettaFold2 provides a powerful new lens through which to view these molecules. It allows for the interpretation of difficult-to-obtain low-resolution experimental data by providing a high-quality structural model to build upon. It enables the study of evolutionary relationships between membrane proteins across species by comparing their predicted structures. It can even help engineer novel membrane proteins for synthetic biology applications, such as creating new biosensors or designing cells that can efficiently produce biofuels.

Of course, this is not the final chapter. The developers are the first to note that challenges remain. Very large membrane protein complexes, proteins with unusual topologies, and the dynamic movements these proteins undergo—their conformational changes—are still difficult to model with perfect fidelity. The next frontiers will involve integrating these static snapshots with data on how these machines move and function in real time. Furthermore, the ethical imperative for open access to such powerful technology is clear. The team has committed to making RosettaFold2 available to the global research community, ensuring that this tool accelerates progress for all of humanity, not just a select few.

The release of RosettaFold2 marks a pivotal moment. It is a testament to the fact that in science, a breakthrough is rarely an ending. It is an invitation. AlphaFold2's stunning achievement invited the world to envision a new era of structural biology. The team at the University of Washington has accepted that invitation and extended it further, specifically to the most challenging and medically relevant corner of the proteome. They have not just kept pace; they have carved a new path. The protein design revolution is now fully underway, and its next act will be written not just in water, but in the complex, crucial, and no-longer-so-hidden world of the cell membrane.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025