In the intricate world of plant biology, few phenomena are as fascinating as the concept of immune priming, particularly through systemic acquired resistance (SAR). At the forefront of this research stands Arabidopsis thaliana, the humble thale cress, which has served as an indispensable model organism for unraveling the molecular intricacies of how plants defend themselves against pathogens. While the biochemical pathways of SAR have been mapped with increasing precision over the past decades, a deeper, more enigmatic layer of regulation has emerged: the role of epigenetics. This heritable yet reversible control of gene expression, without alterations to the DNA sequence itself, is now recognized as a fundamental pillar of how plants "remember" past infections to mount a faster and more robust defense in the future.

The journey of a plant's immune response begins at the site of local infection. When a pathogen breaches the outer defenses, a complex cascade is triggered. The recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) leads to PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI), often sufficient to halt minor invasions. However, more sophisticated pathogens deploy effector proteins to suppress PTI, necessitating a stronger countermeasure. This comes in the form of effector-triggered immunity (ETI), a highly specific and frequently hypersensitive response that sacrifices a few cells to contain the threat. It is from the aftermath of this localized ETI that SAR is born. The dying cells act as beacons, generating a suite of signaling molecules.

Key among these mobile signals are salicylic acid (SA), its derivative methyl salicylic acid (MeSA), and the recently characterized pipecolic acid (NHP) and its glycerol ester. These compounds travel through the plant's vasculature, disseminating a "danger alert" to systemic, unchallenged tissues. This long-distance communication is the first step in preparing the entire organism for a potential secondary infection. The reception of these signals in distant leaves initiates a transcriptional reprogramming, priming defense-related genes for rapid activation. For years, the scientific focus was on the transcription factors that bind to the promoters of these genes to induce their expression. But a persistent question remained: how is this primed state maintained over time, sometimes even throughout the plant's life cycle, and in some cases, passed to the next generation?

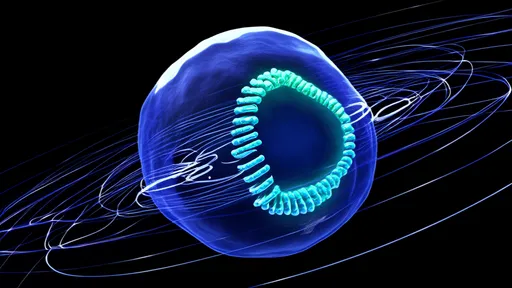

The answer appears to lie in the intricate tapestry of the epigenome. Epigenetic modifications provide a molecular memory system, a way to bookmark sections of the genome for quick access. In the context of SAR, this involves three primary mechanisms: DNA methylation, histone modifications, and the action of non-coding RNAs. DNA methylation, typically associated with gene silencing when it occurs in promoter regions, plays a nuanced role. In Arabidopsis, a reduction in DNA methylation (hypomethylation) at specific defense gene loci, such as those involved in the SA pathway, is often correlated with a primed state. This demethylation opens up the chromatin structure, making the genes more accessible to the transcriptional machinery and allowing for a swifter response upon subsequent challenge.

Perhaps even more critical are the modifications to histone proteins, around which DNA is wound to form chromatin. The N-terminal tails of histones are subject to a vast array of chemical tags—methyl groups, acetyl groups, phosphates, and more—that act like flags, instructing the cellular machinery to either open or compact the chromatin. In SAR, two modifications are particularly prominent: histone acetylation and methylation. The addition of acetyl groups by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) neutralizes the positive charge of histones, loosening their grip on DNA and promoting an open, transcriptionally active chromatin state (euchromatin). This is crucial for the expression of primed genes.

Conversely, the role of histone methylation is exquisitely context-dependent. The addition of three methyl groups to lysine 4 on histone H3 (H3K4me3) is a well-established mark of active promoters and is found at elevated levels on defense genes in primed Arabidopsis plants. This mark recruits proteins that facilitate transcription. On the other hand, trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3) is a repressive mark, associated with facultative heterochromatin and gene silencing. The dynamic balance between these activating and repressing marks helps to fine-tune the primed response, ensuring that defense genes are poised but not constitutively active, which would be energetically costly for the plant.

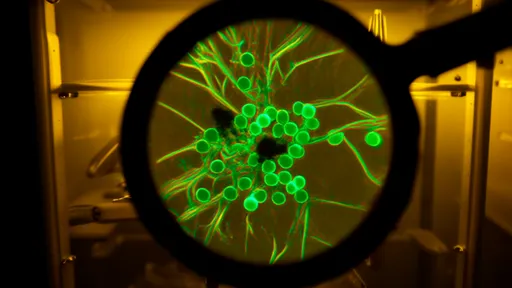

The establishment and maintenance of these epigenetic landscapes are not random; they are directed by the initial biochemical signals of SAR. The NPR1 protein, a master regulator of SA-mediated signaling, plays a dual role. Not only does it act as a coactivator for transcription factors in the nucleus, but it also recruits histone-modifying enzymes to defense gene promoters. For instance, NPR1 interacts with HATs to promote histone acetylation, directly linking the SA signal to chromatin remodeling. Furthermore, the oxidative burst and changes in cellular redox state that accompany infection can influence the activity of enzymes involved in DNA and histone modification, adding another layer of regulation.

The most astounding implication of this epigenetic control is the potential for transgenerational inheritance of resistance. There is growing evidence that the primed state, inscribed as epigenetic marks, can sometimes be transmitted through meiosis to the offspring. This means the progeny of an infected Arabidopsis plant can exhibit a heightened resistance to pathogens they have never directly encountered. This process likely involves the bypassing of epigenetic reprogramming that typically occurs during gamete formation and embryogenesis, allowing a subset of histone modifications or small RNAs to survive and instruct the re-establishment of the primed state in the next generation. This represents a form of Lamarckian inheritance, where an acquired trait (resistance) is passed on, providing a clear evolutionary advantage.

However, this system is not without its checks and balances. Energetically, maintaining a globally primed state is expensive. Therefore, plants have evolved mechanisms to reset the epigenome. DNA methyltransferases and histone deacetylases (HDACs) work to erase the priming marks over time or in the absence of further threat, returning the plant to a basal state of readiness. This ensures that valuable resources are not perpetually allocated to defense at the expense of growth and reproduction. The interplay between priming and resetting creates a dynamic and adaptable memory system, allowing the plant to invest in immunity wisely based on its environmental history.

In conclusion, the story of systemic acquired resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana has evolved from a purely biochemical narrative to a deeply epigenetic one. The plant's immune memory is not stored in a static ledger but in a dynamic, living chromatin landscape that can be written, read, and rewritten. The priming of defense genes through altered DNA methylation and a carefully orchestrated array of histone modifications provides a sophisticated mechanism for balancing the costs and benefits of immunity. This epigenetic basis of SAR underscores the remarkable adaptability and complexity of plants, revealing a stratum of regulation that ensures their survival in a world teeming with microbial threats. As research continues, leveraging this knowledge could pave the way for novel agricultural strategies, breeding crops with naturally enhanced and heritable disease resistance, reducing our reliance on chemical pesticides.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025